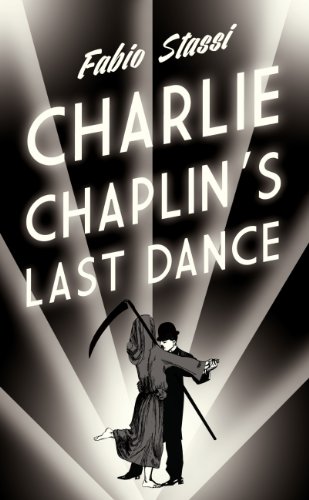

Charlie Chaplin’s Last Dance.

Reviewed by Other Words Books first ever guest reviewer, Adam Weller.

As a person who prides himself on an encyclopaedic knowledge of Chaplin’s life and art, I was curious when presented with the opportunity to review this novel dressed in the clothes of an autobiography by Italian author Fabio Stassi, who has won the Vittorini Prize for best first novel, also the Palmi prize and the Coni Prize. The fact that Signor Stassi is a respected and prize-winning author gave me the fortitude to tackle this book with an open mind.

The book is held together by a simple premise that makes you want to keep reading, even though we know how it all turned out. On Christmas Eve 1972, Charlie is visited by Death. As an 82 year old man Charlie wants to remain alive so that he may see his youngest son Christopher grow up (who is a boy of 10 at this point). Charlie makes a pact with Death; if he can make Death laugh, then he lives another year and has the opportunity to see Christopher grow. Also, Charlie uses this “bonus” time to chronicle his life in a personal letter to his son. Naturally, we can expect the year in which his luck runs out.

Imagine a cross between Bergman’s The Seventh Seal and The Twilight Zone.

Anybody anticipating much in the way of biography/autobiography in this book will be disappointed. But that is not a bad thing. Initially I was a little disgruntled that the author took so many liberties but the more I read, the more I realised that it didn’t really matter. Stassi takes us on a mostly fictional journey through Charlie’s life. Certainly, the most familiar facts are there but these are incidental, maybe to remind us that the author hasn’t actually forgotten about whom he writes! Indeed, I feel that Stassi has used Charlie as a literary coat hanger on which to hang a lifetime of memories. And why? Because for a period of time in the 20th Century Charlie Chaplin was the most famous man in the world. The tramp character he created spoke to us universally, no matter where we were in the world or whatever our status. We see ourselves in that little tramp, he is a canvas for our feelings. And this is where the concept of facing Death works so well. Death is as universal as Chaplin’s little tramp.

Chaplin’s (fictionalised) story between Death’s visits mainly concerns his time as a young man travelling across North America, holding down a variety of jobs, becoming adept at them and moving on before they become stale to him. Many of these professions are odd choices; an embalmer’s, a printing press, taking full responsibility for directing a film with no references… But it somehow all works in its oddness. And this all takes place before his first meeting with Mack Sennett, at whose Keystone Studios he first made his fortune.

Central to the book is the claim that a circus worker called Arlequin was the inventor of the first movie camera, a man who fell into obscurity. (There is more about him later in the book). Another central character who is seemingly always present but never there is a circus acrobat called Eszter, a woman who Charlie goes in search of with disappointing results. A memorable section of the book is when Charlie makes a pilgrimage to Youngstown where Eszter settled and makes the acquaintance of Eszter’s old friends, with whom she opened a flower shop (Stassi of course makes reference to the final scene in Chaplin’s 1931 film City Lights, the tramp’s emotional scene with the blind flower seller who can finally see him after her eye operation. That scene is wisely unresolved). Youngstown is quite effectively depicted as a small minded, racist town who regularly beat and taunt their migrant population. Charlie receives the full force of this bigotry.

It is very telling that much of the book centres around Charlie’s time with a circus troupe. When Stassi recounts Chaplin’s experience of making his film The Circus in 1928, it is an extremely miserable experience. In real life it was a difficult time for Chaplin. He was going through his second divorce and legend has it that his black curly hair had turned white overnight. But the book recounts this time also as an artistic failure. In the fictionalised version Chaplin reads a scathing review of The Circus and becomes obsessed by it, always carrying it about with him on his person. He becomes persona non grata in the entertainment industry and the public turn against him. In real life Chaplin actually did face similar times in the 1940s due to a paternity case (acquitted) and being called to face the House Un-American Activities Committee with the charge of being a communist. McCarthyism was on the rise, and Chaplin was eventually expelled from the United States in 1952. But I digress.

The manner in which Charlie is presented as an elderly man between the “autobiography” segments and the clumsy way in which he desperately tries to make Death laugh are poignant to read and a reminder that time strips us all of our abilities in the end.

Without wishing to reveal any of the story beyond these details, the matter of Arlequin, the movie camera he invented, Eszter the acrobat and even Death himself are all intertwined.

Death finally comes to take Charlie away on Christmas Eve 1977. This time, Charlie is ready for it and faces the event with a calm, almost embracing manner. (The pedant in me needs to stress that Chaplin actually died in his sleep in the early hours of Christmas Day).

If you are well familiar with Chaplin’s life then you may appreciate this attempt to present it in an alternative and largely fictional way. If you are not too familiar with his life, then it would be wise to simply enjoy it as the novel it is.